This topic takes on average 45 minutes to read.

There are a number of interactive features in this resource:

Human biology

Human biology

Every day you meet millions of pathogens in your daily life – why aren’t you constantly ill? The human body has many different defence mechanisms against pathogens. They all depend on recognising foreign material and destroying or, at the very least, inactivating the pathogen.

The human body has a number of adaptations that either prevent the easy entry of pathogens into the body or destroy pathogens as soon as they get inside, before they can cause an infection. For example:

Tears are salty and contain the enzyme lysozyme – both help destroy pathogens

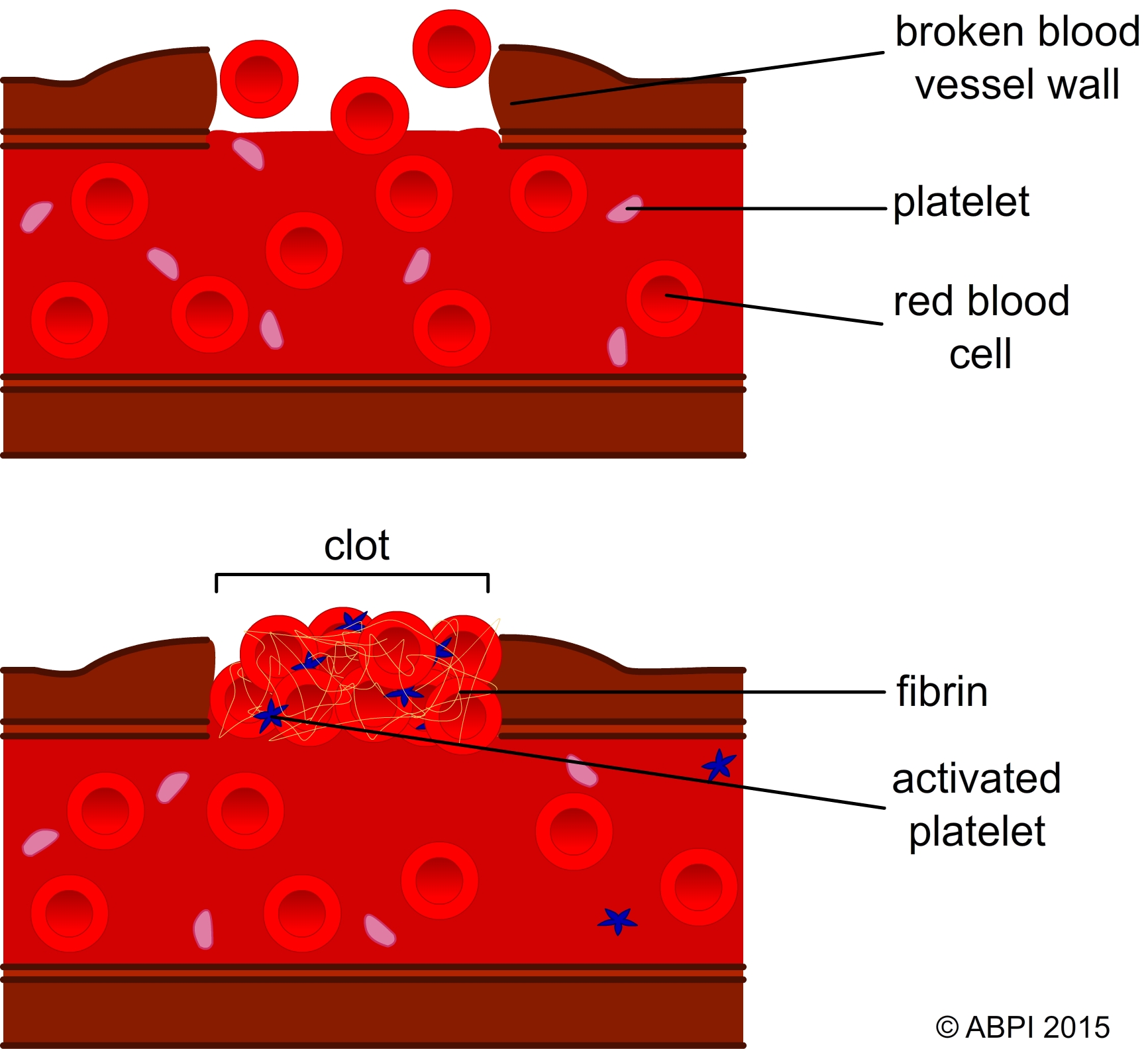

The clotting and healing process that protects the body from the entry of pathogens through an open wound.

The cell surface membranes are the site of cell identification systems. There are glycoproteins and glycolipids (proteins and lipids with short carbohydrate sections attached to the molecules) and these, along with some membrane proteins, act as antigens identifying one cell to other cells. For example this system enables the cells of the immune system to identify pathogens, cells from other organisms of the same species (eg after an organ transplant), abnormal body cells (eg cancer cells) and toxins produced by pathogens. It is also key in the non-specific responses of the body to invading pathogens.

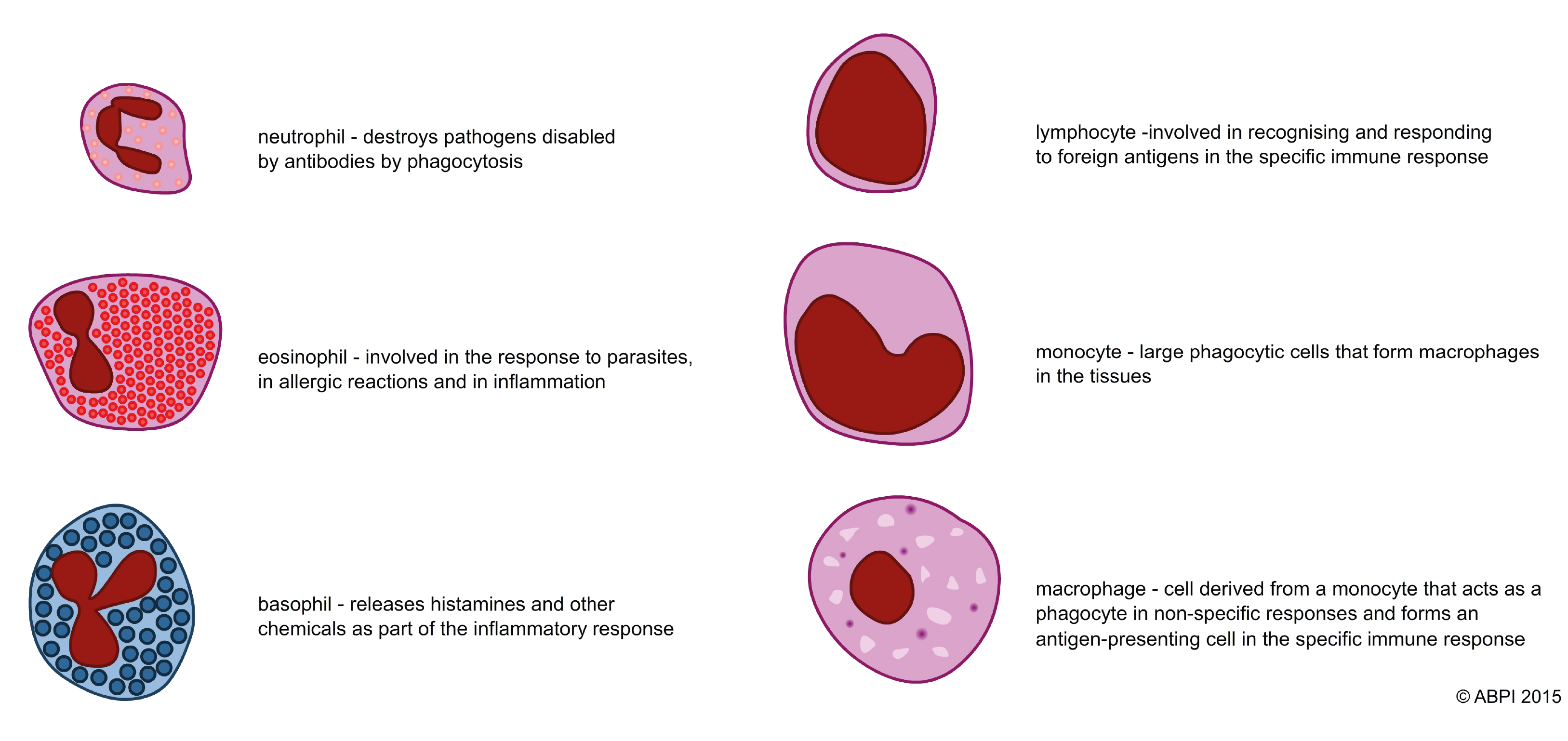

Non-specific responses to infection are usually triggered either by body cells breaking down and releasing chemicals, or by pathogens that have been labelled by the specific immune system. Many of the non-specific responses depend on the many different types of leucocytes (white blood cells). The different cells can be recognised both by their appearance and their functions.

Lymphocytes are one of the most important types of white blood cells and make up 18-42% of circulating blood cells. They play a crucial role in the specific immune response, as will be discussed in the following pages.

These include:

This rash shows typical inflammation.

(Photo credit: CDC)

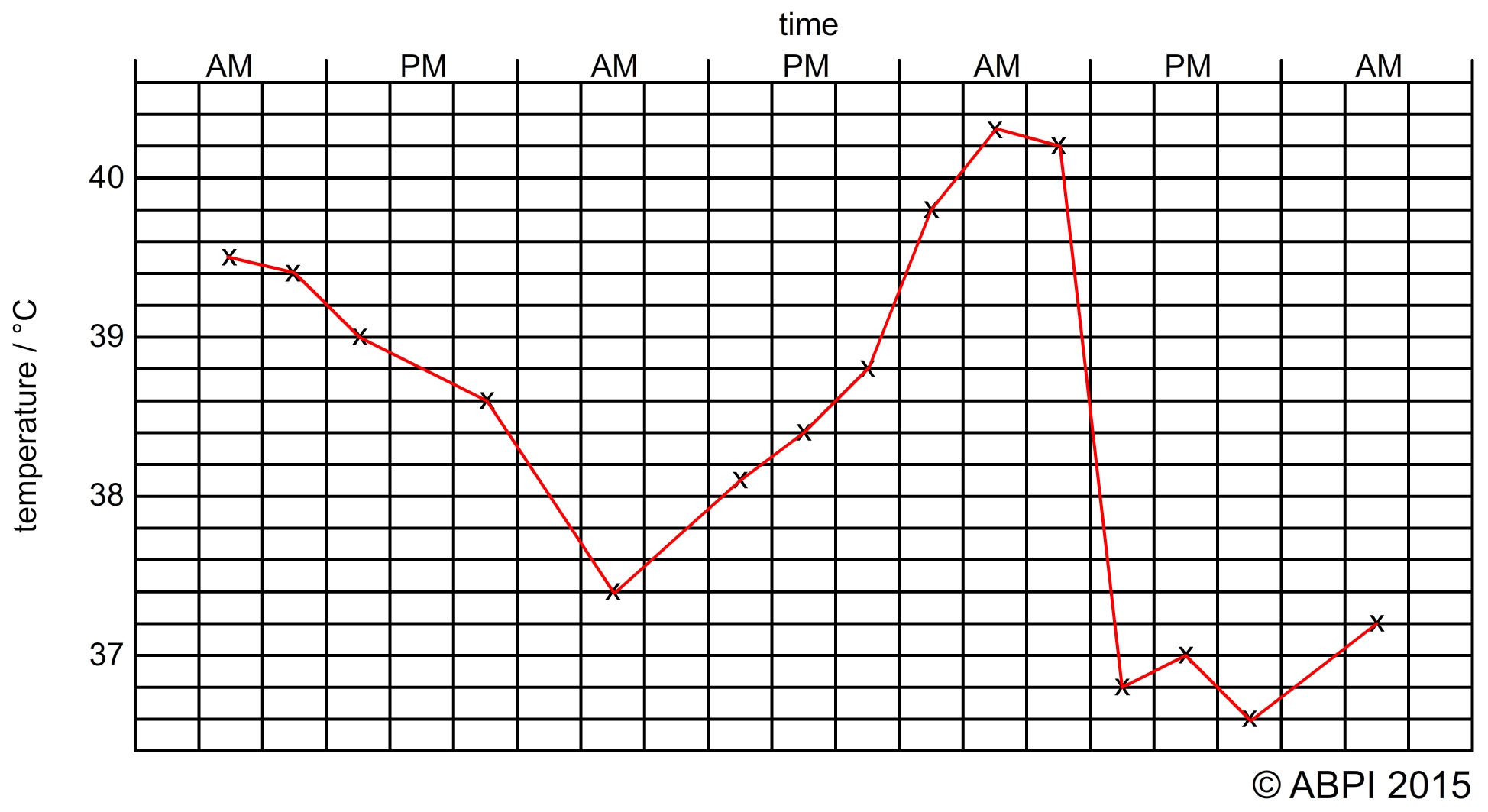

A raised temperature helps fight infection in two ways:

We monitor temperature carefully when someone is ill because if a fever goes too high it can cause damage or be fatal - over 40°C enzymes start to denature and there can be permanent tissue damage or even death

Phagocytosis: this involves white blood cells that engulf and digest pathogens and any other foreign material in the blood and tissues. Phagocytes engulf the pathogen into a vesicle called a phagosome. This fuses with a lysosome and the enzymes break down the pathogen. Phagocytes are very important in both the non specific responses to infection and the specific immune response.

Neutrophils make up 70% of the leucocytes in the blood, but each neutrophil can only ingest a few pathogens before it dies.

Macrophages make up about only about 4% of the leucocytes in the blood. They can digest enormous numbers of pathogens because they can renew the digestive enzymes in their lysosomes, which neutrophils cannot do. Cells called monocytes move to infected tissues and become macrophages, so there are lots of macrophages in the tissues where they are needed.

The pus that sometimes forms in spots or infected cuts is a build-up of dead cells, mainly neutrophils. The dead neutrophils give the pus its yellowish-white colour.